Water Bugs and Salmon – Introducing Aquatic Macroinvertebrates

If you like salmon, then you better like water bugs. Without them we wouldn’t have salmon.

Bugs. Love them, hate them, they play a vital role in all environments. This includes rivers, streams, ponds, lakes and other aquatic areas. Today we are going to dive into the world of aquatic macroinvertebrates.

The term macroinvertebrates refer to animals that you can see with your naked eye that do not have a backbone. Aquatic macroinvertebrates refer to the ones that live at least partially within aquatic environments such as rivers, ponds and lakes.

Some aquatic macroinvertebrates such as water beetles can leave the water and fly to other locations. And others like dragonflies spend part of their lifecycle in the water and then leave the water as adults. But others spend their whole lives in the water.

While aquatic macroinvertebrates are often ignored by most people, or viewed as annoying pests, many of the more charismatic species like salmon, rely on them to survive. If you support salmon, then you better support water bugs.

Aquatic macroinvertebrates can also be used as indicators for water quality. Certain types like stoneflies for example, need cool, moving water to thrive. But others like fly larvae can often be found in warmer and more stagnant water.

Aquatic Macroinvertebrates Role in Aquatic Ecosystems

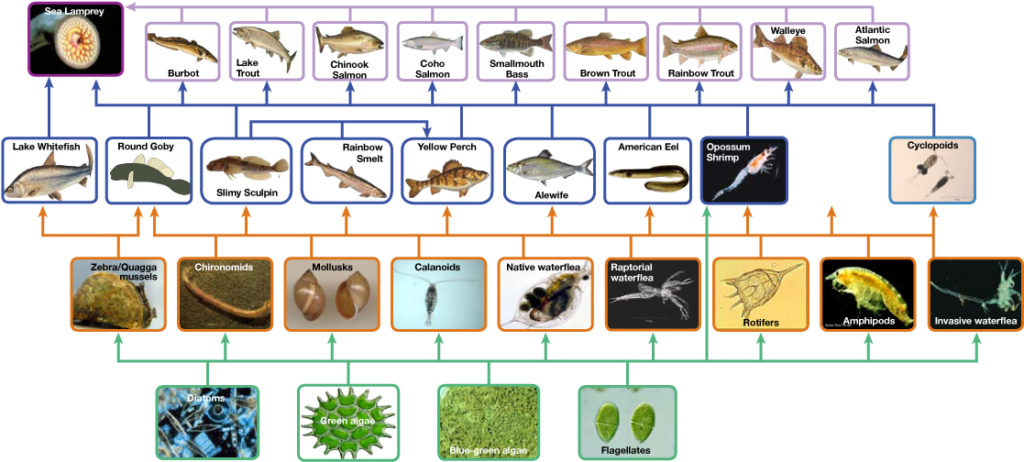

To help us understand the role of aquatic macroinvertebrates in the aquatic environment, let’s take a moment to review the concept of the food chain or food web.

You might remember this from school. It shows how nutrients move through an ecosystem. Starting with the plants, moving up through the critters that eat the plants, and then the critters that eat those, and so on.

In the real world, these sorts of interactions can get very complicated, which is why we sometimes use the term food web instead of food chain. But it’s a good starting point for this discussion.

Aquatic macroinvertebrates fall into a few different places within this food web. Some of them are herbivores that feed off algae and larger aquatic plants. Aquatic snails are a common type of herbivore found in aquatic environments.

Others aquatic macroinvertebrates are filter feeders that filter nutrients and microscopic life from the water. These include freshwater muscles which are a very important part of our aquatic environments here in western Washington.

You will also find shredders and decomposers in most of our aquatic environments. These are aquatic macroinvertebrates that break down fallen leaves, and other organic materials that fall into the water. Caddisflies are a common example, though some are herbivores and some are even predators!

Remember, life is complex!

Shredders and decomposers often form the base of the food chain in our aquatic environments. Small rivers and streams are often shady with steady flows if they are healthy and surrounded by tall trees and shrubs. In these environments you often find very little in the way of aquatic plants outside of algae on rocks and logs.

But all those leaves, branches, logs, and other organic material that fall into the water provide a constant food source for the shredders and decomposers.

These aquatic environments are still dependent on the productivity of plants, just a bit more indirectly than shallow, sunny ponds and lakes that often have lots of aquatic vegetation.

And then finally you have the aquatic macroinvertebrates that are predators and eat other macroinvertebrates, small fish, and other aquatic life. Dragonflies are a common example of a type of predatory aquatic macroinvertebrate.

Their larval stage or nymph hatch from eggs laid in the water. Dragonfly nymphs are active hunters and can spend several months to over a year in the water depending on the species.

And all these different types of aquatic macroinvertebrates are eaten by various critters. From amphibians to salmon and many others, aquatic macroinvertebrates provide food for all sorts of other animals.

Without a healthy population of macroinvertebrates, you don’t get a healthy abundance of wildlife. The smallest critters with the largest populations are often the foundation of an ecosystem after the plants.

Salmon and Aquatic Macroinvertebrates

Here in western Washington State, a lot of work is being done to support and restore the populations of salmon in our waters. This has been a core part of my work as a restoration ecologist and habitat biologist for the last 14+ years.

But more and more in my work, I find myself being drawn to the smallest life like aquatic macroinvertebrates.

Without these little water bugs, you don’t have salmon. As you may know, salmon start their life cycle as eggs laid in redds in rivers and streams.

The newly hatched salmon called alevins still have their egg yolk attached to them, and they hide in the gravels. But after a month or so, that egg yolk is gone, and the young salmon leave the gravel as fry to start looking for food.

That food will consist of various aquatic macroinvertebrates that change over time as the salmon fry grows and matures. Eventually the fry grow enough to be called smolts and spend some time in estuary environments where they transition to saltwater while still eating aquatic macroinvertebrates.

Without enough aquatic macroinvertebrates, the young salmon don’t grow quickly from a lack of food and can struggle to survive and make the transition to the ocean.

But it isn’t just a one-way relationship where the salmon eat the aquatic macroinvertebrates. When the salmon return as adults to the river or creek they hatched in they have grown substantially by feeding on marine life.

When they die after spawning or on the journey up, all sorts of wildlife feed on their bodies. This includes aquatic macroinvertebrates. This releases large amounts of nutrients from the marine environment in the freshwater and upland environment.

This helps trees and forests grow and thrive and also supports the macroinvertebrates that will support the next generation of salmon.

Nutrients flow through the environment in a cycle and aquatic macroinvertebrates are a key part of that cycle.

Supporting Aquatic Macroinvertebrates and Key Takeaways

Try exploring ponds, rivers, lakes and other aquatic environments in your area. Some common ones that you might find are caddisflies, stoneflies, dragonflies, water skippers, water beetles, and aquatic worms. But there are so many more like small freshwater crustaceans and mussels.

And while I focused mostly on the importance of aquatic macroinvertebrates to salmon, they also support all sorts of other life. Without them, the aquatic ecosystems just don’t function.

So how can you support aquatic macroinvertebrates?

Don’t clear vegetation growing near or in bodies of water assuming they are native. This includes leaving any fallen trees or other debris in the water. Wood is good!

Plant native trees and shrubs near bodies of water if they aren’t already there.

Don’t use chemicals to kill the aquatic macroinvertebrates. This includes pesticides but also keeping oils and other pollutants out of our waters by keeping them out of stormwater runoff.

Don’t clear or drain wetlands or seasonal wet areas. These may seem marginal, but if planted with native plants, left un-mowed, then you can support habitat for all sorts of seasonal aquatic life. Consider adding logs and other woody debris to these areas too.

On my own property I have restored a seasonal stormwater stream into over a third of an acre of wetlands with multiple stream channels, small islands, and lots of ponds. The result has been a habitat that supports tons of songbirds, amphibians and other wildlife that weren’t there before we started this effort.

You can work with your local government biologists or conservation districts if you have questions about what is allowed in your area. But generally, seasonally wet areas without fish will be easier to work in. But you are always welcome to plant native plants around streams, rivers and other waterbodies. Planting native plants is a great easy option and then just avoid removing native plants that are already there and leaving logs and branches that fall into the water.

The main thing is to be curious about the aquatic macroinvertebrates that live in your area and then do what you can to support them.

This article was a fairly quick overview of these important critters. But there are a lot of details that I left out. Check out this report from the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife to learn more about Pacific salmon and aquatic macroinvertebrates. You can jump to page 30 if you just want to read about aquatic macroinvertebrates.

And if you want to start learning how to identify the different types of aquatic macroinvertebrates, then here are some resources to help you get started:

About Autistic Nature

Thank you for taking the time to read this article about aquatic macroinvertebrates and their interactions with salmon.

My name is Daron and I’m the person behind Autistic Nature. Autistic Nature is a weekly newsletter mostly about nature and reconnecting with it but also about supporting Autistic people.

I’m an Autistic person and an Autistic self-advocate. I’m also a habitat biologist and restoration ecologist with well over a decade of work experience designing and implementing restoration projects and being a voice for nature.

If you enjoyed this article, please take a moment to share it with someone you know. This is a great way to get the word out and help people learn about Autistic Nature.

You can find me over on BlueSky where I share pictures of my work as a restoration ecologist and habitat biologist, talk about supporting Autistic people, and share a bit about Star Trek.

And please consider supporting Autistic Nature as a paid subscriber. While the core content will always be free, I will start making some special fun articles relating to what I’m doing on my own property and also a bit about Star Trek for paid subscribers.

Any revenue brought in through Autistic Nature will be used to support the ongoing restoration work on my own property and support some of my other special interests. Embracing and supporting special interests is a core way to support Autistic people.

But you can also subscribe as a free subscriber and you will still get access to my weekly articles.

Thank you again for reading this article! Time to go look for bugs!